|

| John Ngugi, in action during the last of his 5th World Cross Country victories, in Boston, in the year 1992. Getty Images www.iaaf.org |

It is hard to believe now, Cross Country, once in the Olympic Games schedule, used to be immensely popular all over the world. It started as a British nations contest but gradually more European countries, the

Great expectations were created in the Madrid la Zarzuela ” venue, because of that debut, especially around the Ethiopian team performance. The East African powerhouse had been back to the Olympic Games, in Moscow 10.000 metres riveting match against Finnish athletes, was still fresh. Among the members of that memorable 1-3-4, Miruts Yifter and Mohamed Kedir were present and so was steeplechase bronze medallist Eshetu Tura.

Their performance in Madrid Ethiopia on Gateshead mud, while Some Muge grabbed the bronze for the first Kenyan individual medal ever. Between them, Carlos Lopes won the silver. The Portuguese veteran was in his best form ever and no runner could match him, neither in the two following editions of the World Cross Champs, nor in the 1984 Olympic Marathon, which he won at age 37. Ethiopia

|

| Bekele Debele edges Some Muge, Carlos Lopes (hidden), Antonio Prieto, Alberto Salazar and Robert de Castella at 1983 World Cross Country Championships, held in Gateshead http://www.elatleta.com / http://ourathletes.blogspot.com/ |

The 1986 edition was to be held in

After 3 kilometres of warming up, three Kenyans, Sisa Kirati, Some Muge and John Ngugi went to the front, increasing dramatically the pace. One of them, the debutant Ngugi kept that brutal outburst and soon was more than 60 metres ahead of the field. Alberto Cova, who was no less than current Olympic, World and European champion tried to respond, but it was in vain. The Kenyan national champion was gaining more and more distance, with a far from elegant but highly effective style of running. A small group with four more Kenyans, Ethiopians Bekele Debele and Abebe Mekonnen, and United States Ethiopia

Ngugi displayed similar tactics under similar weather at Warsaw-87 but, this time, his mate Paul Kipkoech went with him until the finish line. The defending champion won the sprint by a whisker. The same duo again won gold and silver in the next edition of the championships, held in Auckland

But the question is: how Kenya

Of course, Ethiopia 10.000 metres , was a shadow of himself, running throughout the final without conviction, having no answer to Schildhauer’s final kick and eventually fading to 9th, one place ahead of Bekele Debele. One can wonder how the national team trained for that championship. Only Kebede Balcha with his silver medal in the marathon could save the honour of his country.

No other big victory was obtained in the next eight years. However, it does not mean necessarily lack of talent. Ethiopia

Abebe Mekonnen was the flag bearer of a whole lost generation. Being no less than the inmortal Abebe Bikila’s nephew, great things were expected from him. For instance, besides doing well in Cross Country, he triumphed in many prestigious Marathons as Rotterdam , Boston , Beijing , Tokyo or Paris

Anyway, most of these athletes missed the chance of taking part in the most important championship of all, the Olympic Games, since Ethiopia

|

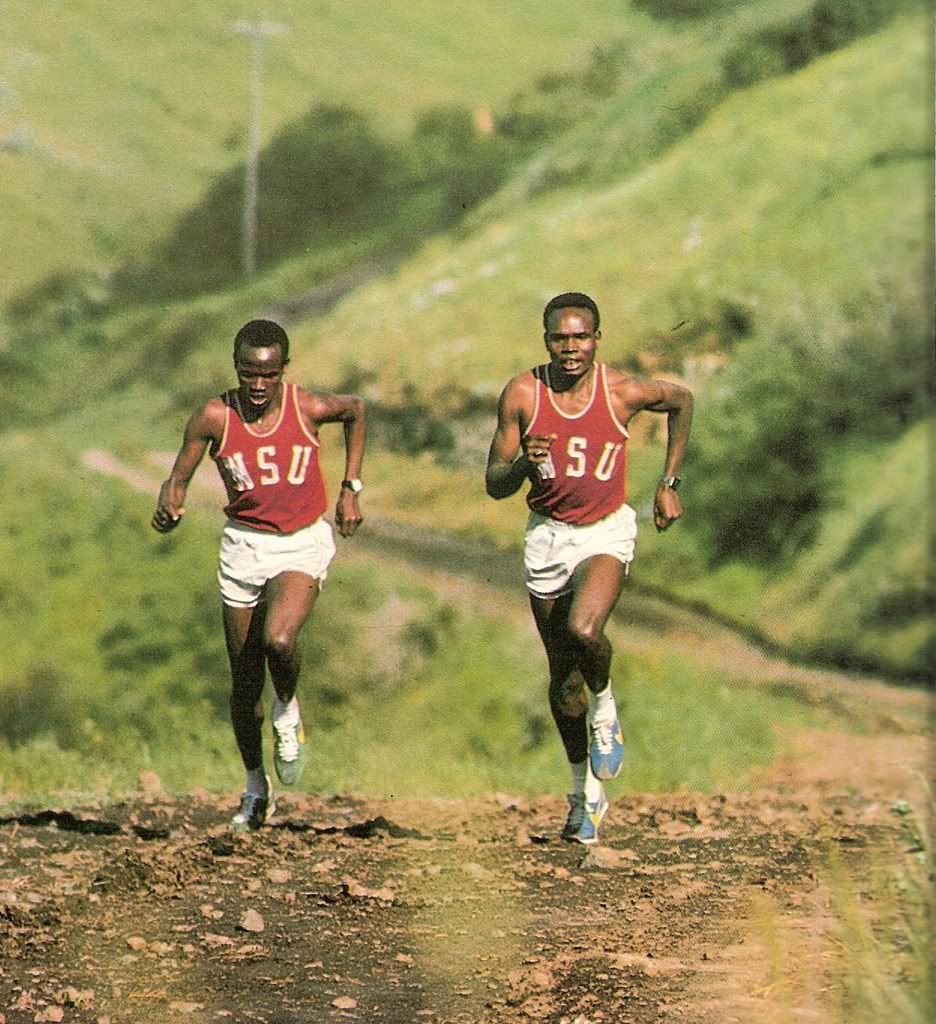

| Henry Rono (r), training with college mate Samson Kimobwa www.elatleta.com |

Kenya athletics had had to overcome a similar crisis the previous decade. Its boycott to Montreal-76 and Moscow-80 deprived a whole generation of the chance of chasing their dream in the Olympic Games. Athletics were languishing in Kenya and in words of John Manners “US College scholarships helped keep track from dying altogether in Kenya” (2) Fred Hardy from Richmond had pioneered since the sixties, with Kip Keino’s collaboration, the initiative of bringing talented African runners to help American Universities shine in national championships. (3) All the young Kenyan promising runners as Samson Kimobwa, Henry Rono, Mike Musyoki, Sosthenes Bitok or Wilson Waigwa were there to develope their athletics career. Grassroots work in their homeland had come to nothing and Kenyan athletics authorities were not doing either their ambassadors athletes life easy, owing their passports, trying to control every one of their moves, cashing every earning they had and causing them problems to compete in European meetings. Henry Rono, one of the most gifted distance runners ever, who achieved the unbelievable feat of smashing four world records (3000, 5000, 10.000 metres and steeplechase) in only 81 days, as a young Washington State collegian (4), ended precociously his career victim of alcoholism, altogether alienated. He had become a moneymaker for agents, promoters and Kenyan authorities and his dream of competing for a medal in the Olympic Games was just unattainable.

Kenya returned to a major global competition on the track for 1983 Helsinki World Championships. Its results were not better than Ethiopians: a seventh placement in a final was its highest achievement. No man was entered in the 10.000 metres event. At that point, African athletes seemed to have become mentally inferior to European or American ones. Nevertheless, things improved in Los Angeles Olympic Games the following year. Among other high note performances, Julius Korir, brougth back to Kenya the steeplechase gold medal his predecessor in Washington State University, Henry Hono, was unable to fight for. Anyway, results and image were still a world away from the ones at Mexico and Munich Olympic Games.

However, it was not at the track but at the Cross Country specialty that a radical change in approach was going to change the face of Kenyan athletics forever. Two men, Mike Kosgei and John Ngugi were the responsible of this Kenyan revolution which shocked the athletics world and encouraged and inspired all future coaches and runners in the country. (2)

Initially, it was German Walter Abmayr who coached the national team and fostered Kenya Kenya finished a close second to Ethiopia

|

| John Ngugi and Paul Kipkoech at 1987 Warsaw World Cross Champs. Bob Martin /Getty Images/ All Sport http://www.life.com/image/1233156 |

After Abmayr’s depart, Kosgei took over and started to work his own way. Firstly, he moved the camp to Embu, on the Eastern slopes of Mount Kenya , far away from friends, girlfriends and family who used to disturb the concentration in Nyeri. Secondly, he increased the number of workouts from 2 to 3 daily, including both high intensity and high mileage. This killer preparation meant a radical rupture with tradition in Kenya

Ngugi, a Kikuyu, born in May 1962, who had migrated to the Nandi district as he was 3 years old, decided to join the Army forces in 1984, where he was employed as a mechanic. (5) Soon he started to build up a solid reputation. He used to wake up in the night and run for hours with the help of a torch. Then he would went to sleep and in the morning would join the others for the scheduled training. (2) Ngugi participated at Los Angeles Olympic Trials and the following year got his first international medal at the Easter and Central

Mike Kosgei brutal workout regime did not seem enough to fit him, because he used to run on his own on a longer path, which was to be known as “the Ngugi route”. After his victory at the 1986 World Cross Champs, other athletes would join him the following year and, by 1988 he was leading the whole team on the “Ngugi route”. The sensational results in successive championships would have the consequence of spreading the example everywhere in Kenya

More and more training camps were founded and the work at grassroots level was reinvigorated. It really helped the newly launched IAAF World Junior Championships, which could serve as starting point for teen careers and at the same time as a showcase, where talents could be scouted by agents and international Universities. Brother Colm O’Connell chose the first Kenyan team for the inaugural championships in 1986, held in Athens Kenya 10.000 meters champion Peter Chumba would never start a professional career, while others like Wilfred Kirochi and Peter Rono would become celebrated stars. These championships were also a starting point for African women athletes. Kenyan and Nigerian girls, won three and four medals respectively, the first ones they had collected in a global championship, in 1986, and Derartu Tulu, in the 1990 edition, with her gold medal at 10.000 metres would open the Ethiopian women road to success.

O’Connell would also pioneer this incorporation of African female to the athletics circuit. The legendary coach, who had come from Ireland to St. Patrick School

|

| Lydia Cheromei wins the World Junior Cross Champs at the record age of 13 Gray Mortimore/ Getty Images/ All Sports |

Brother O’Connell first training camp was the Sing'ore summer High School 3000 metres at 1991 World Championships, just one year before Derartu Tulu’s gold medal at Barcelona Olympics, moved to Japan for athletics, far away from family and all the men who could control her life. She was the admired role model for future star cousins Sally Barsosio and Lornah Kiplagat. " We sang songs about her. We would walk around her house. When I would run after a goat, I would think "run like Susan". Susan was like a really big thing." (7) Brother O’Connell also mentored olympians Selina Chirchir, Hellen Kimaiyo and Lydia Cheromei. (8) The latter rose to fame, after winning the World Junior Cross Championships in 1991 at age 13! After several dropouts and comebacks, Cheromei is still running competitively today as a marathoner. Since 1991, East African women have only lost once in the senior World Cross Country and are unbeaten in the junior race, which was incorporated to the athletics calendar to their glory in 1989.

Dedication and hard work were paying off, and Kenya proved to themselves and to the rest of the world they were ready to become the distance powerhouse in Track and Field, with their excellent performance at 1987 Rome World Championships and 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Paul Kipkoech started the Kenyan party in Rome in the 10.000 metres , playing his part as announced by coach Kip Keino: “We will take some risks and see what happens” (9). Kipkoech came past the whole field, to run lap 5 in 60 seconds, then surged away again twice to unsettle the field and eventually went alone in lap 14, running the second half in an incredible 13:24 split, to win for more than 10 seconds. Always second to Ngugi in Cross Country, he could show in Rome

Billy Konchellah also was plagued by several illnesses, all along his career, but in spite it could achieve two world championships victories in 1987 and 1991 in the 800 metres with his majestic and effortless stride. Douglas Wakiihuri, who had gone on his own initiative to Tokyo

Despite, being Kipkoech and Konchellah absents, Kenya 800 metres ; Julius Kariuki continued the tradition in the steeplechase, romping home just one tenth of a second shy of Henry Rono’s world record; Peter Rono was the first of a long lineage of Brother Colm O’Connell pupils in winning an Olympic gold medal, in the 1500 metres distance; and finally, John Ngugi could translate his Cross Country hegemony to the track, in the 5000. In Rome

Ngugi won his fourth Cross Country title in a row the following year in Stavanger Kenya still kept the team title but Khalid Skah of Morocco Boston

|

| Brother Colm O'Connell in his Athletics School in Iten John Gichigi/ Getty Images http://beijing2008.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/05/20/the-irish-priest-and-the-long-distance-runners-in-the-kenyan-highlands/ |